Get Healthy!

- Posted February 18, 2022

Risk for Parkinson's Disease Falls After a Heart Attack

A new study hints that heart attack survivors may have an unusual advantage over other people: a slightly lower risk of developing Parkinson's disease.

Researchers found that compared with similar people who had never suffered a heart attack, survivors were 20% less likely to be diagnosed with Parkinson's over the next 20 years.

The big caveat: The findings do not prove a true "protective" effect. And even if that were the case, no one would advocate letting your heart health go to ward off Parkinson's.

"This is an epidemiology study, and it can't prove cause and effect," said James Beck, chief scientific officer for the nonprofit Parkinson's Foundation.

There could be various reasons that heart attack was linked to a lower risk of Parkinson's, according to Beck, who was not involved in the study.

Plus, he noted, the risk reduction was quite small.

The findings -- published Feb. 16 in the Journal of the American Heart Association -- do add to evidence that certain risk factors for heart disease, including smoking and high cholesterol, are paradoxically tied to a lower risk of Parkinson's.

Parkinson's disease affects nearly 1 million people in the United States, according to the Parkinson's Foundation.

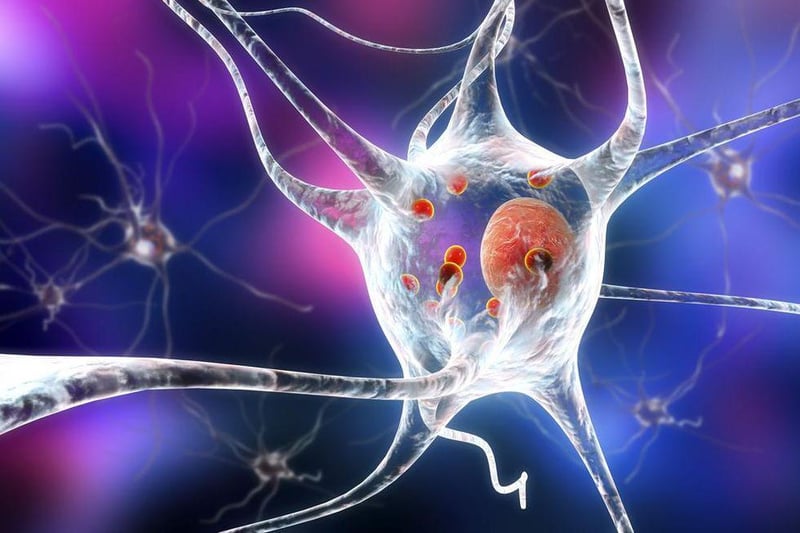

It is a brain disease that over time, destroys or disables cells that produce dopamine, a chemical that helps regulate movement and emotional responses.

The most visible symptoms of Parkinson's are movement-related -- tremors, stiff limbs and coordination problems -- but the effects are wide-ranging and include depression, irritability and trouble with memory and thinking skills.

"We still don't know the cause of PD, why it progresses, or how to stop it," Beck said.

There are, however, some known risk factors for the disease. Older age is one, as are certain environmental factors -- including a history of head trauma and job exposures to pesticides or heavy metals.

"But most people with those exposures do not develop Parkinson's," Beck pointed out.

In general, he said, researchers suspect the disease arises from a complex interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental factors.

As for protective factors, some research suggests that regular exercise and a healthy diet -- like the traditional Mediterranean diet -- may be associated with a lower Parkinson's risk.

Then there are the studies with more puzzling results: Some have linked certain risk factors for heart disease and stroke -- smoking, high cholesterol and diabetes -- to lower odds of developing Parkinson's.

It's possible that those findings help explain the current ones, according to lead researcher Dr. Jens Sundbøll of Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark.

His team used a Danish national registry to identify nearly 182,000 people who suffered a first-time heart attack between 1995 and 2016. They compared those patients with more than 900,000 individuals matched for age and sex, but with no history of heart attack.

Over the 21-year study period, 0.9% of heart attack survivors developed Parkinson's disease. Another 0.1% were diagnosed with secondary parkinsonism -- where Parkinson-like symptoms arise due to other causes, such as certain medications.

After the researchers weighed other factors, including various medical conditions, they found that heart attack survivors were 20% less likely to develop Parkinson's than the comparison group.

Similarly, the survivors had a 28% lower risk of secondary parkinsonism.

Going into the study, the researchers were unsure what they would find. In past research, Sundbøll said in a journal news release, heart attack survivors showed an increased risk of certain other brain disorders -- including stroke and a form of dementia caused by impaired blood flow to the brain.

The current findings, he said, suggest that Parkinson's risk is "at least not increased" following a heart attack.

Beck said the relationship between heart health and Parkinson's "remains unresolved."

While some studies hint at protection from things like smoking or high cholesterol, he said, they leave open the "chicken-and-egg question."

Parkinson's disease, Beck explained, has a long "prodromal" phase -- a period in which people may have certain symptoms of the disease, but it has not yet fully manifested.

And there is evidence, for example, that cholesterol levels may decline during that early phase. That could make it look like higher cholesterol is protective against Parkinson's.

Similarly, Beck said, the connection between smoking and lower Parkinson's risk may not reflect an effect of smoking: One theory is that, possibly due to the loss of dopamine, people in the early stages of Parkinson's are less prone to addiction.

"There may be other things going on here that we don't yet understand," Beck said. "The bottom line is, the brain is incredibly complex."

More information

The Parkinson's Foundation has an overview on Parkinson's disease.

SOURCES: James Beck, PhD, senior vice president and chief scientific officer, Parkinson's Foundation, New York City; Journal of the American Heart Association, online study and news release, Feb. 16, 2022